From irritant to tear-gas: the early story of why a toxic agent became non-lethal

Posted: June 17, 2020 Filed under: Chemical | Tags: 1925 Geneva Protocol, Chemical warfare, International Humanitarian Law, Law enforcement, Riot control agent, World War 1 2 CommentsWith the recent international attention to riot control agents (RCA) people have raised the question how their use against protesting civilians can be legal when the toxic agents are internationally banned from battlefields.

Framed as such, the question is not entirely correct. In my previous blog posting I argued that outlawing RCAs for law enforcement and riot control based on the above reasoning may run into complications in the United States because the country still identifies operational military roles for irritants on the battlefield in contravention of the Chemical Weapons Convention.

This article sketches the convoluted history of harassing agents as a means of combat and a police tool. For hundreds of centuries until the late Middle Ages irritants were part of siege warfare. In the 19th century interest returned because of a new competition between defensive structures and breaching weaponry. Just like in earlier times, toxic fumes could drive defenders from their enclosed positions. The rise of chemistry introduced new compounds with the potential to clear occupants from fortifications.

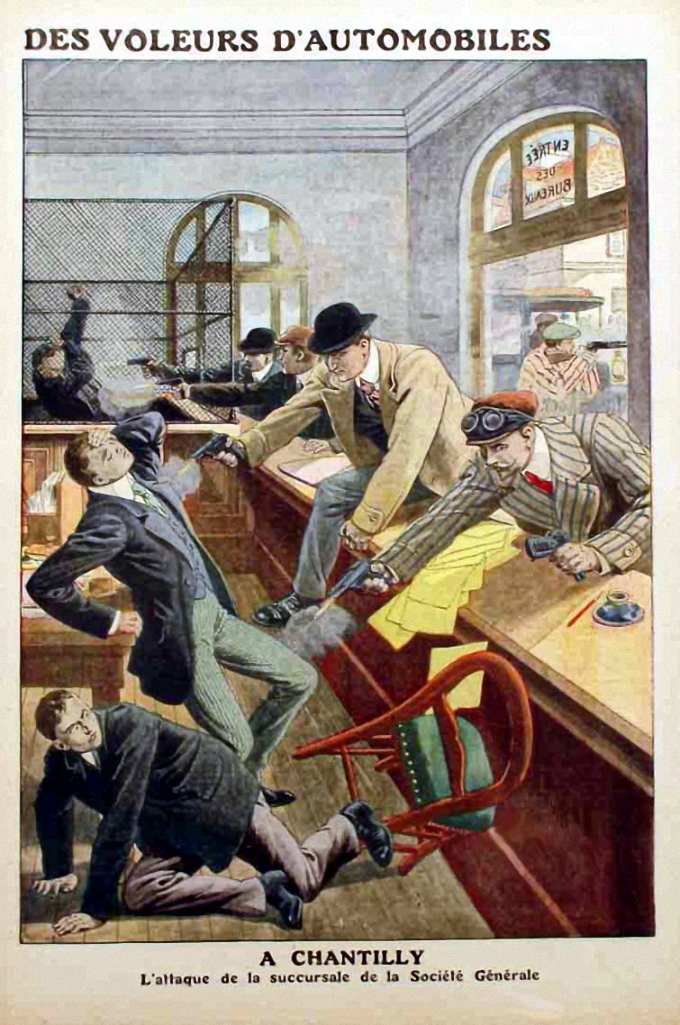

Just before World War 1 French police had to confront a new form of gangsterism. Bandits used the most advanced weaponry and tools not yet available to police officers, they barricaded themselves in buildings, and resisted arrest until their last bullet. To reduce bloodshed, the police investigated alternatives to dislodge the new creed of brigands.

How the Convergence of Science, Industry and Military Art Slaughtered Innocence

Posted: August 30, 2019 Filed under: Chemical | Tags: Belgium, Chemical warfare, Education, Germany, Industry, Science, UK, World War 1 Leave a commentKeynote speach at the CONDENsE Conference, Ypres, Belgium, 29 August 2019

(Cross-posted from The Trench)

Good evening ladies and gentlemen, colleagues and friends,

It is a real pleasure to be back in Ieper, Ypres, Ypern or as British Tommies in the trenches used to say over a century ago, Wipers. As the Last Post ceremony at the Menin Gate reminded us yesterday evening, this city suffered heavily during the First World War. Raised to the ground during four years of combat, including three major battles – the first one in the autumn of 1914,  which halted the German advance along this stretch of the frontline and marked the beginning of trench warfare; the second one in the spring of 1915, which opened with the release of chlorine as a new weapon of warfare; and the third one starting in the summer of 1917 and lasting almost to the end of the year, which witnessed the first use of mustard agent, aptly named ‘Yperite’ by the French – Ypres was rebuilt and, as you have been able to see to, regain some of its past splendour.

which halted the German advance along this stretch of the frontline and marked the beginning of trench warfare; the second one in the spring of 1915, which opened with the release of chlorine as a new weapon of warfare; and the third one starting in the summer of 1917 and lasting almost to the end of the year, which witnessed the first use of mustard agent, aptly named ‘Yperite’ by the French – Ypres was rebuilt and, as you have been able to see to, regain some of its past splendour.

Modern chemical warfare began, as I have just mentioned, in the First World War. It introduced a new type of weapon that was intended to harm humans through interference with their life processes by exposure to highly toxic substances, poisons. Now, poison use was not new.

However, when the chlorine cloud rose from the German trenches near Langemark (north of Ypres) and rolled towards the Allied positions in the late afternoon of 22 April 1915, the selected poisonous substance does not occur naturally. It was the product of chemistry as a scientific enterprise. Considering that the gas had been CONDENsE-d into a liquid held in steel cylinders testified to what was then an advanced engineering process. Volume counted too. When the German Imperial forces released an estimated 150–168 metric tonnes of chlorine from around 6,000 cylinders, the event was a testimonial to industrial prowess. Poison was not a weapon the military at the start of the 20th century were likely to consider. Quite on the contrary, some well-established norms against their use in war existed. However, in the autumn of 1914 the Allies fought the German Imperial armies to a standstill in several major battles along a frontline that stretched from Nieuwpoort on the Belgian coast to Pfetterhausen – today, Pfetterhouse – where the borders of France, Germany and Switzerland then met just west of Basel. To restore movement to the Western front, the German military explored many options and eventually accepted the proposal put forward by the eminent chemist Fritz Haber to break the Allied lines by means of liquefied chlorine. 22 April 1915 was the day when three individual trends converged: science, industrialisation and military art.

This particular confluence was not by design. For sure, scientists and the military had already been partners for several decades in the development of new types of explosives or ballistics research. And the industry and the military were also no strangers to each other, as naval shipbuilding in Great Britain or artillery design and production in Imperial Germany testified. Yet, these trends were evolutionary, not revolutionary. They gradually incorporated new insights and processes, in the process improving military technology. The chemical weapon, in contrast, took the foot soldier in the trenches by complete surprise. It was to have major social implications and consequences for the conduct of military operations, even if it never became the decisive weapon to end the war that its proponents deeply believed it would.

Innocence Slaughtered – Book launch at OPCW

Posted: November 19, 2015 Filed under: Chemical | Tags: Chemical warfare, OPCW, World War 1 Leave a comment Described by Ambassador Ahmet Üzümcü, Director-General of the OPCW, as a ‘remarkable compilation of materials, rich in detail and edited in the finest traditions of highly readable scholarship’, Innocence Slaughtered is a new book that will launch with a panel discussion on 2 December, from 13.00-15.00 at this year’s Conference of States Parties to the Chemical Weapons Convention. Edited by Dr Jean Pascal Zanders, the book features the writings of eleven experts and historians on gas warfare and chemical weapons and is being published to coincide with the first phosgene attack in WWI on 19 December 1915.

Described by Ambassador Ahmet Üzümcü, Director-General of the OPCW, as a ‘remarkable compilation of materials, rich in detail and edited in the finest traditions of highly readable scholarship’, Innocence Slaughtered is a new book that will launch with a panel discussion on 2 December, from 13.00-15.00 at this year’s Conference of States Parties to the Chemical Weapons Convention. Edited by Dr Jean Pascal Zanders, the book features the writings of eleven experts and historians on gas warfare and chemical weapons and is being published to coincide with the first phosgene attack in WWI on 19 December 1915.

The launch event will be a panel discussion with Dr Jean Pascal Zanders, Ambassador Ahmet Üzümcü, Mr Jef Verschoore, Deputy Mayor and Chairperson of In Flanders Fields Museum, Mr Dominiek Dendooven and Dr Leo van Bergen, both chapter authors. They will discuss the immediate impact of gas warfare, before exploring its subsequent effect on the use of science in future conflicts and the struggle to legally ban the use of chemical weapons in future conventions.

Book launch

Date & time: Wednesday, 2 December 2015; 13:00 – 15:00

Location: Ieper Room, OPCW Headquarters, Johan de Wittlaan 32, The Hague, Netherlands

Speakers:

- Ambassador Ahmet Üzümcü, Director-General, OPCW

- Mr Jef Verschoore, Deputy Mayor and Chairperson In Flanders Fields Museum

- Mr Dominiek Dendooven, Researcher, In Flanders Field Museum [Chapter author]

- Dr Leo van Bergen, Independent Researcher [Chapter author]

- Dr Jean Pascal Zanders, The Trench [Book editor and Chapter author]

Publisher’s information sheet. Copies of of the book will be available for purchase.

(A second book launch event will take place at In Flanders Fields Museum, Ypres on Thursday, 10 December.)

Innocence Slaughtered: Introduction

Posted: October 16, 2015 Filed under: Chemical | Tags: Chlorine, Civil society, Disarmament, International Humanitarian Law, OPCW, War, World War 1 Leave a commentInnocence Slaughtered will be published in December 2015

In November 2005 In Flanders Fields Museum organised and hosted an international conference in Ypres, entitled 1915: Innocence Slaughtered. The first major attack with chemical weapons, launched by Imperial German forces from their positions near Langemarck on the northern flank of the Ypres Salient on 22 April 1915, featured prominently among the presentations. I was also one of the speakers, but my address focussed on how to prevent a similar event with biological weapons. Indeed, it was one of the strengths of the conference not to remain stuck in a past of—at that time—nine decades earlier, but also to invite reflection on future challenges in other areas of disarmament and arms control. Notwithstanding, the academic gathering had a secondary goal from the outset, namely to collect the papers with historical focus for academic publication.

The eminent Dutch professor and historian Koen Koch chaired the conference. He was also to edit the book with the historical analyses. Born just after the end of the 2nd World War in Europe, he sadly passed away in January 2012. He had earned the greatest respect from his colleagues, so much so that the In Flanders Fields Museum set up the Koen Koch Foundation to support students and trainees who wish to investigate the dramatic events in the Ypres Salient during the four years of the 1st World War. The homage was very apt: Professor Koch had built for himself a considerable reputation as an author of studies on the 1st World War. Most remarkable: The Netherlands had remained neutral during the conflagration, which adds to the value of his insights.

Death, unfortunately, also ends projects. In the summer of 2014, while doing some preliminary research on the history of chemical warfare, I came across the manuscripts of the chapters that make up the bulk of this book. They were in different editorial stages, the clearest indication of how abruptly the publication project had screeched to an end. Reading them I was struck by the quality of the contents, rough as the texts still were. Together, the contributions also displayed a high degree of coherence.

One group of papers reflected on the minutiae of the unfolding catastrophe that the unleashing of chlorine against the Allied positions meant for individual soldiers and civilians. They also vividly described German doubts about the effectiveness of the new weapon, and hence its potential impact on combat operations. These contributions also reflected on the lack of Allied response to the many intelligence pointers that something significant was afoot. In hindsight, we may ponder how the Allied military leaders could have missed so many indicators. Yet, matter-of-fact assessments of gas use by Allied combatants recur in several chapters, suggesting either widespread anticipation of the introduction of toxic chemicals as a method of warfare or some degree of specific forewarning of the German assault. Gaps in the historical record, however, do not allow a more precise determination of Allied anticipation of chemical warfare. Still, a general foreboding may differ significantly from its concrete manifestation. From the perspective of a contemporary, the question was more likely one of how to imagine the unimaginable. Throughout the 2nd Battle of Ypres senior Allied commanders proved particularly unimaginative. In the end, the fact that German military leaders had only defined tactical goals for the combat operations following up on the release of chlorine, meant that they had forfeited any strategic ambition—such as restoring movement to a stalemated front, seizing the Channel ports, or capturing the vital communications node that Ypres was—during the 2nd Battle of Ypres, or ever after. The surprise element was never to be repeated again. Not during the 1st World War, not in any more recent armed conflict.

The second group of papers captured the massive transformation societies were undergoing as a consequence of industrialisation, science and technology, and the impact these trends were to have on the emergence of what we know today as ‘total war’. Chemical warfare pitted the brightest minds from the various belligerents against each other. The competition became possible because the interrelationship between scientists, industry, politicians and the military establishment was already changing fast. But chemical warfare also helped to effectuate and institutionalise those changes. In many respects, it presaged the Manhattan Project in which the various constituencies were brought together with the sole purpose of developing a new type of weapon. In other ways the competition revealed early thinking about racial superiority that was to define the decades after the Armistice. The ability to survive in a chemically contaminated environment was proof of a higher level of achievement. In other words, chemical defence equalled survival of the fittest. Or how Darwin’s evolutionary theory was deliberately misused in the efforts to justify violation of then existing norms against the used of poison weapons or asphyxiating gases.

During and in the immediate aftermath of the war, opposition to chemical warfare was slow to emerge. In part, this was the consequence of the appreciation by soldiers in the trenches and non-combatants living and working near the frontlines that gas was one among many nuisances and dangers they daily faced as its use became more regular. Defences, advanced training and strict gas discipline gave soldiers more than a fair chance of surviving a gas attack. The violence of total war swept away the humanitarian sentiments that had given rise to the first international treaties banning the use of poison and asphyxiating gases in the final year of the 19th century. Those documents became obsolete because people viewed modern gas warfare as quite distinct from primitive use of poison and poisoned weapons or the scope of the prohibition had been too narrowly defined. By February 1918 chemical warfare had become so regular that a most unusual public appeal on humanitarian grounds by the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) badly backfired on the organisation. Throughout the 1920s the choice between an outright ban on chemical weapons and preparing populations for the consequences of future chemical warfare would prove divisive for the ICRC. In contrast, peace and anti-war movements in Europe campaigned against war in all its aspects and consequently refused to resist one particular mode of warfare before the Armistice. It is instructive to learn that opposition to chemical warfare specifically first arose far away from the battlefields—northern America and neutral Netherlands—and among a group of citizens not directly involved in combat operations: women. And perhaps more precisely, women of science who protested the misapplication of their research and endeavours to destroy humans. Just like the chlorine cloud of 22 April 1915 foreshadowed the Manhattan project, the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom presaged the Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs, who would bring together scientists, academics and political leaders to counter the growing menace of nuclear war and find solutions to other threats to peace and security.

It was clear to me that I should not remain a privileged reader of the manuscripts. They contained too much material and insights that the broader public should have access to. Piet Chielens, curator of the In Flanders Fields Museum, and Dominiek Dendooven, researcher at the Museum, could not agree more, and so a new publication project was born. However, since the centenary of the chlorine attack was only a few months away, reviving the academic product Koen Koch had been working on was initially not an option. So, the decision was to exploit modern communication technologies and produce the volume as a PDF file in first instance. However, by the time the electronic edition was ready for online publication, In Flanders Fields Museum had found a publisher willing and able to produce a formal edited volume before the end of the centenary year of the first modern gas attack. My gratitude goes to Ryan Gearing of Uniform Press for his guidance and concrete assistance in making this book a reality.

Time for preparing this publication was very short. To my pleasant surprise, every author in this volume responded favourably and collaboration over several intense weeks—both in the preparation of the original PDF version and the subsequent book project—proved remarkably gratifying and productive. Some contributors even took the time to introduce me to certain concepts widely accepted among historians, which I, with my background in linguistics and political science, had interpreted rather differently. For the experience in preparing this volume, I indeed wish to thank every single contributor.

22 April 1915 was not just the day when the chlorine cloud rolled over the battlefield in Flanders. It also symbolises the confluence of often decade-old trends in science, technology, industry, military art and the way of war, and social organisation. That day augured our modern societies with their many social, scientific and technological achievements. However, it was also a starting point for new trends that eventually led nations down the path of the atomic bomb and industrialised genocide in concentration camps. It also highlighted the perennial struggle of international law and institutions to match rapid scientific and technological advances that could lead to new weapons or modes of warfare. This volume captures the three dimensions: the immediate impact of poison warfare on the battlefield, the ways in which the events in the spring of 1915 and afterwards shaped social attitudes to the scientification and industrialisation of warfare, and the difficulties of capturing chemical and industrial advances in internationally binding legal instruments. Indeed, there can be no more poignant reminder that our insights into the trends that brought the chlorine release 100 years ago are crucial to our understanding of trends shaping our societies today and tomorrow.

Yes, the world has moved on since the 1st World War, even if the use of chlorine in the Syrian civil war one century later may seem to challenge the thought. Yet, one institution may unwittingly have come to symbolise the progression. Fritz Haber, the scientific and organisational genius who led Imperial Germany’s chemical warfare effort in 1915, was awarded the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 1918. Typical for the day, the Nobel Committee detached scientific achievement from moral considerations. His contribution to the development of a synthetic fertiliser for agricultural use, for which he got the prize, equally enabled Germany to continue munition production in the face of an Allied blockade denying it access to foreign raw materials. Haber’s part in chemical warfare too fell entirely outside the Nobel Committee’s considerations. Ninety-five years later, in 2013, the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons received the Nobel Peace Prize for its progress in eliminating the scourge of chemical warfare. The decision represented a strong moral statement, for it reflected the (Norwegian) Nobel Committee’s views that today chemistry, and science in general, should serve peaceful purposes. Therefore it is indeed painfully paradoxical that the successful elimination of the most toxic substances developed and produced for warfare has resulted in the return of chlorine, today a common industrial chemical, as a weapon of choice in the Syrian civil war that started in 2011.

We indeed still experience the consequences of 22 April 1915: this dichotomy between the application of science and technology for life and their mobilisation for war continue to characterise our societal development today. This realisation explains why I thought that the papers, initially prepared under the guidance of Professor Koen Koch, should see the light of day. Particularly now.

Jean Pascal Zanders

Ferney-Voltaire, October 2015

Innocence Slaughtered – Forthcoming book

Posted: September 25, 2015 Filed under: Chemical | Tags: 1899 Hague Declaration, 1925 Geneva Protocol, Chemical warfare, international law, World War 1 1 CommentThe introduction of chemical warfare to the battlefield on 22 April 1915 changed the face of total warfare. Not only did it bring science to combat, it was both the product of societal transformation and a shaper of the 20th century societies.

This collaborative work investigates the unfolding catastrophe that the unleashing of chlorine against the Allied positions meant for individual soldiers and civilians. It describes the hesitation on the German side about the effectiveness, and hence impact on combat operations of the weapon whilst reflecting on the lack of Allied response to the many intelligence pointers that something significant was afoot.

It goes on to describe the massive transformation that societies were undergoing as a consequence of industrialisation, science and technology, and the impact these trends were to have on the emergence of what we know today as ‘total war’. Chemical warfare pitted the brightest minds from the various belligerents against each other and in some ways this competition revealed early thinking about intellectual superiority that was to define the decades after the Armistice. The ability to survive in a chemically contaminated environment was proof of a higher level of achievement. In simple terms, chemical defence equalled survival of the fittest.

- Edited by Dr Jean Pascal Zanders

- Introduction by Ahmet Üzümcü, Director-General of the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW)

- To be published in December 2015

Table of Contents

- Ahmet Üzümcü (Director-General Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons): Preface

- Jean Pascal Zanders: Introduction

- Jean Pascal Zanders: The Road to The Hague

- Olivier Lepick: Towards total war: Langemarck, 22 April 1915

- Luc Vandeweyer: The Belgian Army and the gas attack on 22 April 1915

- Dominiek Dendooven: 22 April 1915 – Eyewitness accounts of the first gas attack

- Julian Putkowski: Toxic Shock: The British Army’s reaction to German poison gas during the Second Battle of Ypres

- David Omissi: The Indian Army at the Second Battle of Ypres

- Bert Heyvaert: Phosgene in the Ypres Salient: 19 December 1915

- Gerard Oram: A War on Terror: Gas, British morale, and reporting the war in Wales

- Wolfgang Wietzker: Gas Warfare in 1915 and the German press

- Peter van den Dungen: Civil Resistance to chemical warfare in the 1st World War

- Leo van Bergen and Maartje Abbenhuis: Man-monkey, monkey-man: Neutrality and the discussions about the ‘inhumanity’ of poison gas in the Netherlands and International Committee of the Red Cross

- Jean Pascal Zanders: The road to Geneva

After 99 years, back to chlorine

Posted: April 22, 2014 Filed under: Chemical, War | Tags: Chemical warfare, Chlorine, CWC, OPCW, Syria, World War 1 Leave a commentToday is the 99th anniversary of the first massive chemical warfare attack. The agent of choice was chlorine. About 150 tonnes of the chemical was released simultaneously from around 6,000 cylinders over a length of 7 kilometres just north of Ypres. Lutz Haber—son of the German chemical warfare pioneer, Fritz Haber—described the opening scenes in his book The Poisonous Cloud (Clarendon Press, 1986):

The cloud advanced slowly, moving at about 0.5 m/sec (just over 1 mph). It was white at first, owing to the condensation of the moisture in the surrounding air and, as the volume increased, it turned yellow-green. The chlorine rose quickly to a height of 10–30 m because of the ground temperature, and while diffusion weakened the effectiveness by thinning out the gas it enhanced the physical and psychological shock. Within minutes the Franco-Algerian soldiers in the front and support lines were engulfed and choking. Those who were not suffocating from spasms broke and ran, but the gas followed. The front collapsed.

The impact of this gas attack surprised the German Imperial troops too. Their cautious advance behind the chlorine cloud, their hesitation in the confusion about what was happening despite having secured their initial objectives within an hour, and their halt after darkness fell meant that they almost immediately lost the strategic surprise. They would never regain it.

A first generation warfare agent in worldwide industrial application

How ironic it is that today, almost a century later, the latest chemical warfare allegations in the Syrian civil war concern chlorine once again. Everybody knows about the dangers of the chemical element, but nobody really considers it any longer as a militarily useful agent. At least not in standard warfare scenarios.

Chlorine and derived products are in massive industrial production. According to the World Chlorine Council, there are more than 500 chlor-alkali producers at over 650 sites around the globe, with a total annual production capacity of over 55 million tonnes of chlorine. Based on the low threat assessment and its wide relevancy to the chemical industry and trade, the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC) does not even list it in Schedule 3 of toxic chemicals (Phosgene, another widely used chemical and World War 1 agent, is).

An oversight by the CWC negotiators? Hardly. Books on the toxicology and treatment of chemical warfare agents published between 1992—year of successful conclusion of the negotiations—and 1997—year of entry into force of the CWC—hardly mention chlorine. Chemical Warfare Agents, edited by Satu Somani (Academic Press, 1992), presents a few scattered references, mostly in relation to other agents or public health. Another book featuring the same title, written by Timothy Marrs, Robert Maynard and Frederick Sidell (Wiley, 1996), gives it a four-line acknowledgment in the opening historical section. And the monumental Medical Aspects of Chemical and Biological Warfare, edited by Frederick Sidell, Ernest Takafuji and David Franz (Office of the Surgeon General, US Army, 1997), accords it about two pages out of 721 in a subsection entitled ‘Historical War Gases’.

Today, chlorine is mostly viewed as a public health or environmental hazard resulting from occupational exposures, industrial accidents or the malfunctioning of pool chlorination systems.

Back to World War 1

It goes without saying that during and after World War 1 perceptions of chlorine as a combat agent were quite different. Despite having been replaced by much more potent toxic chemicals, belligerents released chlorine gas until the final month of the war. Considering that the first contingents of the American Expeditionary Forces arrived in Europe in June 1917, but saw their first major military engagements in May/June 1918, the US War Department registered and examined 838 ex-service men who had been gassed with chorine (and survived their experience). A closer medical examination of 98 victims to assess the long-term effects of exposure suggests that all US chlorine casualties were affected between July and October 1918. It is interesting to note that Maj. Gen. Harry Gilchrist, Chief of the Chemical Warfare Service, and Philip Matz, Chief of the Medical Research Subdivision of the Veterans’ Administration, devoted half of their medical study, The Residual Effects of Warfare Gases (War Department and US Government Printing Office, 1933), to chlorine, mustard being the other agent of their investigation.

Their description of chlorine remains interesting, because it departs from its utility as a warfare agent, rather than as a public health hazard. The element is almost 2.5 times heavier than air, which means that it will cling to the surface and sink into depressions. At 15° C liquefaction requires 4-5 atmospheres pressure. Upon release at 25° C, one litre of liquid chlorine will yield 434 litres of chlorine gas. Moisture stimulates the element’s chemical action, so the liquid gas must be thoroughly dehydrated for storage in steel cylinders.

Concentration and length of exposure both play a role in the physiological action of chlorine and their effects on humans and animals. The authors noted that ‘a concentration of 1–100,000 of chlorine gas is noticeable, 1–50,000 may cause inconvenience, while a concentration of 1–1,000 may produce death after exposure for five minutes’. (The numbers correspond to 0.01 mg/ml; 0.5 mg/ml and 1mg/ml respectively.) Experimental studies on dogs (carried out to determine the types of lesions various concentrations of chlorine will produce) showed that the animals died within 72 hours from acute effects at concentrations of 2.53 mg/l and higher. These concentrations were labelled as lethal. A small percentage of the animals recovered within a week. A concentration of 1.9–2.53 mg/l increased the recovery rate markedly, whereas dosages below the 1.9 mg/l were rarely fatal. Recovery rates were markedly faster at lower concentrations.

Concentrations required for injury and death are relatively high. For comparison, in the section on mustard (dichlordiethyl sulphide) Gilchrist and Matz deemed this oily compound to be 50 times more toxic than chlorine. It can be deadly in concentrations from 0.006 to 0.2 mg/l, but they considered 0.07 mg/l at an exposure of 30 minutes to be the lethal concentration.

Rewind to March 2013

Syria, just like any other country with a relatively advanced chemical industry, produced chorine in large quantities before the civil war. Readers will recall that early reports of chemical attacks at Khan al-Assal, west of Aleppo, in the middle of March of last year mentioned a strong smell of chlorine. To the east of Aleppo, there was a chlorine production facility (which the Jubhat Al Nusra, a jihadist rebel group ideologically similar to Al Qaeda, reportedly took over in December 2012). However, accounts also mentioned scores of fatalities, which would be inconsistent with a chlorine-filled rocket warhead. I have always been sceptical about those claims, precisely because of the agent’s chemical properties and physiological action. At the time, descriptions did not fit the claimed agents, whichever these might have been.

The need to compress the agent into a liquid has ramifications for delivery: the container must be sufficiently strong to withstand several atmospheres of pressure, and if dropped from an aircraft, sufficiently thin for the skin to break open. It must also be large enough so that a lethal concentration can be built up for a sufficiently long time. Given that humans smell chlorine at very low concentrations, the chances that they will remain at the site of impact are remote. The element is also not colourless; in fact, its name derives from the ancient Greek ‘khloros’, meaning pale green.

The same goes for rocket delivery of the warfare agent. Shells were attempted during World War 1, but this method for chlorine discharge was quickly abandoned in favour of much more potent munition fillings, such as phosgene.

So, it would be good to get more details on the recent incidents and review them in the light of possible chlorine delivery. Please note that I do not deny the possibility of toxic incidents over the past few weeks, but I would just like to see the various facts reconciled with the claimed chain of events. Given that Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov and French President François Hollande have once again waded into the controversy, politicisation of the ‘truth’ cannot be far away, alas.

Back to where it all started

So, as we reflect on that fateful 22 April in 1915, the sad thought is that chlorine is back, or at least, that people feel that chlorine is back as a possible lethal combat agent.

Allegations fly, but if confirmed, the incidents would be the first acts of chemical warfare committed involving a state party to the CWC. If Syria’s accusation of insurgent use is correct, then the government has every opportunity to demand an investigation from the OPCW and request assistance. If the insurgents’s claim of government use is correct, as non-state actors they cannot request the OPCW anything. However, any state party to the convention can demand an investigation of alleged use by the OPCW, and the Syrian government has no right of refusal (Verification Annex, Part XI). The opposite would be a serious material breach of its treaty obligations and tantamount to an admission of guilt. Or, the states parties can determine that the claims are insufficiently substantiated to warrant an investigation. In which case, it would be nice if they all were to sing the same tune.

So, which way shall the international community have it? The principal long-term casualty of those political games might be the CWC, even though, admittedly, we are still far away from the death knell that 22 April 1915 sounded for the 1899 Hague Declaration (IV, 2) concerning asphyxiating gases.

Postscript

Several recent reports have suggested that because chlorine or other toxicants, such as riot control agents or incapacitants, are not listed in one of the schedules, they are not covered by the CWC. This is a major error. Any chemical which through its chemical action on life processes can cause death, temporary incapacitation or permanent harm to humans or animals is a chemical weapon, according to Article II of the CWC. This is the default position. There are only four categories of purposes (Art. II, 9), under which a toxic chemical would not be considered a weapon.

First modern chemical warfare: 98th anniversary today

Posted: April 22, 2013 Filed under: Chemical, History, War | Tags: Battle of Ypres, Chemical warfare, Chlorine, History, World War 1 4 CommentsOn this day, 22 April at 5 p.m. CET the first major chemical attack in modern warfare began 98 years ago, when German Imperial Forces released between 150–168 tonnes of chlorine gas from almost 6000 cylinders along a 700-metre front near the Belgian town of Ieper.

In a study for SIPRI published in 1997, I summarised the opening of the 2nd Battle of Ypres as follows:

Modern chemical warfare is regarded as having begun on 22 April 1915. On that date German troops opened approximately 6000 cylinders along a 7-km line opposite the French position and released 150–168 tonnes (t) of chlorine gas. Tear-gas (T) shells were also fired into the cloud and at the northern flank, the boundary between French and Belgian troops. Between 24 April and 24 May Germany launched eight more chlorine attacks. However, chemical warfare had not been assimilated into military doctrine, and German troops failed to exploit their strategic surprise. Chemical weapon (CW) attacks in following weeks were fundamentally different as they supported local offensives and thus served tactical purposes. In each case the amount of gas released was much smaller than that employed on 22 April, and crude individual protection against gas enabled Allied soldiers to hold the lines.

Prior to the April 1915 use of a chlorine cloud, gas shells filled with T-stoff (xylyl bromide or benzyl bromide) or a mixture of T-stoff and B-stoff (bromoacetone) had been employed. In addition, as early as 14 February 1915 (i.e., approximately the same period as CW trials on the Eastern front) two soldiers of the Belgian 6th Division had reported ill after a T-shell attack. In March 1915 French troops at Nieuwpoort were shelled with a mixture of T- and B-stoff (T-stoff alone had proved unsatisfactory). In response to the British capture of Hill 60 (approximately 5 km south-east of Ypres), German artillery counter-attacked with T-shells on 18 April and the following days. In the hours before the chlorine attack on 22 April the 45th Algerian Division experienced heavy shelling with high explosive (HE) and T-stoff.

Such attacks continued throughout the Second Battle of Ypres. Although Germany overestimated the impact of T-shells, on 24 April their persistent nature appears to have been exploited for the first time for tactical purposes. Near Lizerne (approximately 10 km north of Ypres) German troops fired 1200 rounds in a wall of gas (gaswand) behind Belgian lines to prevent reinforcements from reaching the front. The park of Boezinge Castle, where Allied troops were concentrated, was attacked in a similar manner.

Just a small thought that almost a century later we are still worrying about the possibility of the use of gas in war.